A Review of College Party Culture and Sexual Assault

A review of Lindo, Jason M., Peter Siminski, and Isaac D. Swensen (2018). College party culture and sexual assault. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10, pp. 236-265. A fixed effect analysis

By: Julian Olsen-Pendergast

This review essay will be considering the paper "College Party Culture and Sexual Assault" published in 2018 by Jason M. Lindo et al. The authors examine the role of college partying and the ensuing elevated levels of intoxication, and the increases in the number of sexual assault cases. This paper provides a comprehensive statistical analysis showing that alcohol consumption at college parties leads to an increased prevalence in sexual assault cases. Further research by the World Health Organisation has shown that if an individual participates in the consumption of alcohol, it has an influence on their aggression levels towards others (Beck and Heinz, 2013). In a further study Minczek et al, found that no other drug increased violent behaviour in users more than alcohol intoxication. Moreover, they found a large variability aggressive tendencies and levels of intoxication. Suggesting that individuals who display aggression while under the influence are comparatively more violent than those who exhibit aggression while sober (Miczek, 2004). Lastly, in a paper from 1968, Becker found that if either the victim or the aggressor in the case of sexual assault is under the influence of alcohol consumption, the aggressor holds the belief that they are less likely to be punished, thereby increasing the individual's perceived 'incentive' to commit an act of sexual assault. While Kilpatrick et al. found that in only one-third of sexual assault cases, the victims were not under the influence of alcohol prior to or during the incident. While the current literature is mostly centred on the relationship between alcohol consumption and the prevalence of sexual assault cases, it is clear to most that there is a link between the consumption of alcohol and college parties, particularly in the United States. Thus, the motivation of Lindo et al.'s paper was to prove the causal link between partying and the prevalence of sexual assault cases. This review will mainly be focused on the discussion of the econometric methods behind this seminal paper, in addition its limitations.

A challenge faced by the authors was finding data on college parties and their time and location, as there is clearly no dataset describing this. Lindo et al. used the knowledge that in US colleges, there was a link between college football games and college parties. This connection is due to the culture surrounding college football teams and student supporters, with student supporters regularly throwing parties to celebrate their college football team. The data concerning sexual assault cases and their reporting institutions was collected from the widely used, National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). This allows the authors to identify cases that occurred in conjunction with college football games. Using the institutional standardized rape definition, they were able to define the cases in which the victims were college students. This was done through selecting victims between the ages of 17 and 24 years old, thereby selecting the most likely data points of college students. To find cases that potentially could have occurred at post-football game parties the authors selected the cases that occurred from 6:00 AM to 5:59AM on days that held a football game. This was done as most college parties continue over to the early mornings of the next calendar day. Utilizing college football programs and data from ESPN, they constructed a variable called "ESPN-listed television coverage" as a proxy for football games, as all college Division 1A football games are televised on ESPN. Lastly, they noted that due to some universities having a higher propensity to party they must include a variable that controls for this. For this they used the Princeton Review Top Party Schools Ranking. Finally, they used online sources to determine if a college game had a positive or negative predicted outcome, this was done with the intention of looking at “underdog” wins.

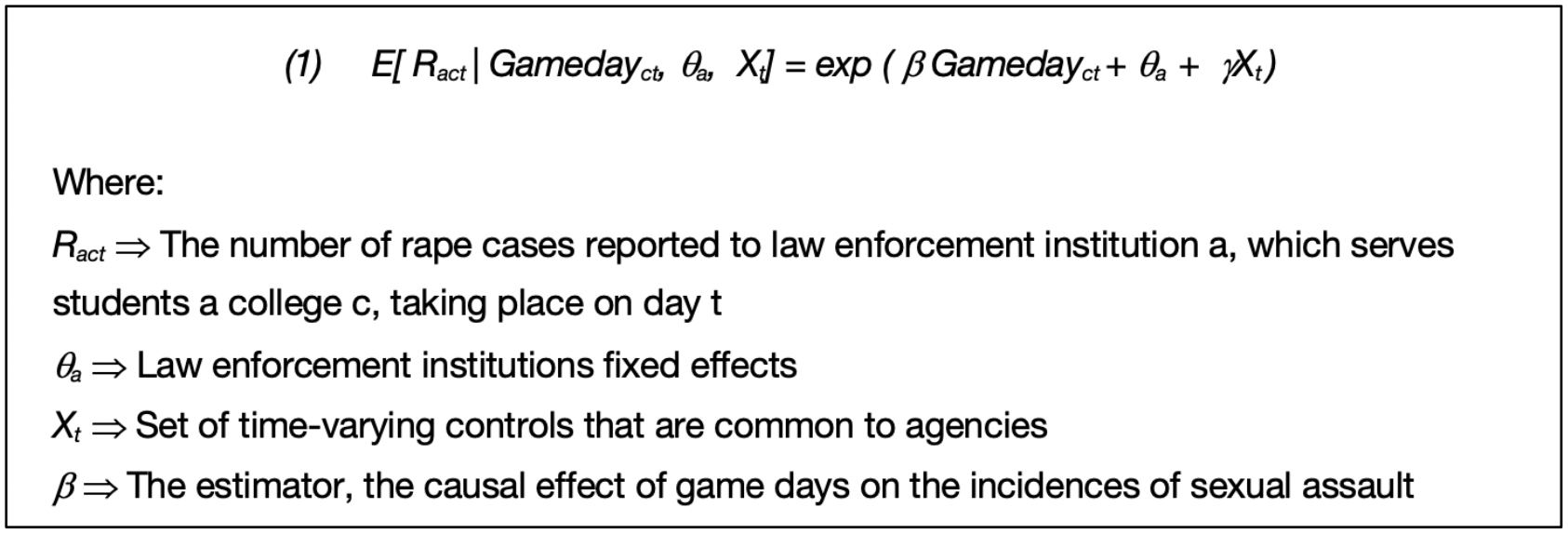

Under these parameters and constraints, the authors constructed a panel dataset consisting of 425,190 observations between the years 1991 to 2012. The authors needed to employ either fixed effects or random effects models to obtain unbiased effects. In this case, the paper used fixed effects to model the relationship between Division 1 football games and instances of rape cases. Using fixed effects in econometric models is generally recognized as a successful and sound method to control for observations that are held constant within each unit. However, this is not without its drawbacks. These drawbacks can cause problems concerning validity, low statistical power, omission bias, and unobserved heterogeneity. The identification parameter was able to leverage the credible random variations in football games. Variables that included the reported incidents of rape to institutions were added to the model. Incorporating fixed effects is essential to manage variations over time and unchanging attributes across agencies. The causal connection between college football games and sexual assault cases is given by:

Equation (1) deals with fixed-effect control variables by incorporating them to counter potential bias, these fixed effects arises from inter-institution disparities and temporal variations. The fixed-effect variables are included to account for the endogenous differences that occur within law enforcement institutions reporting systems, such as the variations in game day occurrences across the sampled colleges and institutions. Lindo et al. used time-varying variable controls, such as the day of the week, case year, and whether the case occurred on a holiday. The variable for the day-of-week fixed effect was added with the intention of accommodating the increase in other weekend partying activities aside from "Football Saturdays", when most games occurred. This addition is vital as most colleges will experience increased levels of alcohol consumption over the weekend regardless of football games. Lastly, by adding the fixed effect of holidays to the models, Lindo et al. aimed to mitigate potential bias that occurred on days when both a football game and a holiday took place, with the same logic applied as above. Additionally, year fixed effects capture annual fluctuations in reports resulting from university organising more and more football games since the 1990’s.

The paper revealed that in cases of a reported surge in the incidence of sexual assault, 28% of them occurred on days when football games took place, within the window of post-football game parties. The impact of these games on the prevalence of cases is particularly noticeable when the football game was held at the college, with cases spiking by over 40% during the parties held after a home game. When the game was held at another college, it resulted in a 15% rise in cases. These persistent patterns are prominently highlighted in the age demographic of 17 to 34, within which the vast majority being assumed to be college students. The causal link between Division 1A football games is a key attribute, with 724 reported cases across 128 colleges during game days, compared to non-game days.

The paper was effective in its application of general intuition to justifiably deselecting the various variables that could have impacted the surge in rape cases during game days. Looking at Table 1, we find a compiled collection of the Reported Incidents per Day arranged into demographics based on age, race, and intoxication. The authors found that in the sample, victims aged between 17-24 experienced a rape case every 19.6 days, with 70% of the victims being white, and 60% knowing their aggressor. Lindo et al. encountered two challenges when it came to the interpretation of the β variable. The study evaluated threats to validity by examining spatial and temporal displacement effects, shifts in the probability of reporting rape cases, and the robustness of the primary results.

Lindo et al. raised the issue of spill-over effects resulting from the temporal and spatial displacement of the model and its impact on the validity of β. When a football game occurs on the home campus, it is evident that along with the increase of local college students in the area, the away team will also bring its own group of college students as fans. This implies that when a football game occurs, there will be an increase in the number of reported cases in the home college's area, and a decrease in the number of cases in the area from which the away team's fans travelled. Consequently, one could potentially expect an increase in the value of β in the home town and the overall effect of β. These spatial displacement effects were compiled in Table 3, where Division 1A and Division 1B schools within a 25- and 50-mile radius were compared. Lindo et al. found no substantial evidence to suggest that a reduction in rape cases in nearby areas was being offset by the predicted cases occurring in the locations of the game day. Alongside these findings in Table 3, Table 4 shows that there was no substantial evidence to suggest a reduction in rape cases on Saturdays without football games during term time and Saturdays during the rest of the year. Findings from Table 2 suggest that when colleges hosted home games, the increase in the prevalence of rape cases was 41%, which is three times higher than the increased reports of away game days. Further analysis into the hourly case reports found that during colleges' home games and the previous night, the prevalence was affected. However, they only found increased prevalence on days that had away games and not the previous night. The authors suggested that this was caused by home teams 'pregaming' or consuming alcohol the night before the game.

Furthermore, it should be added that due to the nature of rape cases, they are statistically under-reported, which is a drawback as the analysis can only be based on reported cases. As mentioned earlier, the Poisson model captures the relationship that Lindo et al. aimed to analyse: the corresponding variations in the number of reported cases, as opposed to the level of cases. For instance, if game days have no effect on the likelihood of a rape case being reported to the corresponding law enforcement institutions, one can still definitively conclude the percentage increase in rape cases with β representing the causal effect of game days on the incidences of sexual assault, under the assumption that the chance of a rape occurring and being successfully reported is not affected, ceteris paribus. However, this variable doesn’t account for the nature of the college culture surrounding football games and their 'Football Saturdays,' which have been shown to encourage larger parties with increased student attendance and, subsequently, a higher level of alcohol consumption. Along with this influx of students, it means that if a case occurs, the victim is less likely to know the aggressor. This is further substantiated by a paper that researched rape cases and the victims' ability to identify the aggressor from Glasgow University (Adams, 2018). In this paper, it was estimated that the chance of identifying the aggressor was over 90%, as opposed to the estimate of 60% by Lindo et al. The variance between these two statistics could very well be attributed to the influx of students at 'Football Saturday' college parties.

Furthermore, Lindo et al. tested whether college game day parties affected the probability of overall crime reports. This was done under the assumption that overall crime reporting would have fluctuations between game days and other days, suggesting that rape cases would follow the same pattern of under-reporting on game days. Lindo et al.'s test concluded that the probability of a rape victim reporting a case was not affected by whether it was a game day. However, this only holds if the assumption of reporting between all crime and rape cases is constant, which it very well might not be.

The heterogeneity of the estimated effects by victim characteristics, offender characteristics, the relationships between victims and aggressors, and the role of alcohol consumption is further addressed in later stages of Lindo et al.'s paper. This deeper exploration allowed the panel data to be divided into college-aged groups. Table 5 illustrates the effect of home and away football game rape cases reported by race, age, and the relationship to the aggressor. Panels A and B illustrate how age and the connection to the aggressor affect rape cases and their statistical probability. Panel C delves into how race affects case statistics, in which Lindo et al. find that race played little to no effect on rape cases.

The concluding tables, 6, 7, and 8, collectively illustrate the effects of division ranking and prominence, college party habits, and predicted game outcomes on rape cases, respectively. In Table 6, the results demonstrate that the increased prevalence of cases on game days is predominantly driven by the higher-ranked Division 1A teams playing amongst themselves. This could be due to the elevated levels of skill and competition creating more hype around the games and, consequently, increasing the levels of alcohol consumption and attendance at ensuing parties. Table 7 found that rape cases increased by 70% on home-game days at party schools, while there was only a 30% increase in case prevalence on away game days at non-party schools. Lastly, the sample heterogeneity between predicted and actual outcomes was discussed in further detail, and Lindo et al. provided additional insight into the relationship between the increase in domestic violence surrounding games. Table 8 concluded, at the 1% level of significance, that the case arrests of intoxication-related crimes and rape cases post wins that were not predicted, i.e., when an upset occurred, saw an increase by 0.27 and 0.32.

To conclude, the paper written by Lindo et al. successfully aimed to prove a causal link between college Division 1 football games and their ensuing parties and the prevalence of sexual assault cases. In their statistical analysis, Lindo et al. provided robust and sound solutions and a thorough understanding of the problems they encountered, demonstrating successful selection methods for their solutions. Overall, their estimates showed that if a college party were to occur, accompanied by an increase in alcohol consumption, the prevalence of a rape case would increase by 28% for individuals aged 17 to 24, under the assumption that these parties had no effect on the rate at which crimes, specifically rape cases, were reported to the appropriate law enforcement institutions.

References

Adams, L., 2018. Sex attack victims usually know attacker, says new study. BBC, [online] Available at: <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-43128350> [Accessed 3 December 2021].

Bindler, A., Ketel, N. and Hjalmarsson, R., 2020. Costs of victimization. Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics, pp.1-31.

Chalfin, A., Danagoulian, S. and Deza, M., 2021. COVID-19 has strengthened the relationship between alcohol consumption and domestic violence (No. w28523). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Heinz, A., Beck, A., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Sterzer, P. and Heinz, A., 2013. Cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms of alcohol-related aggression. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(7), pp.400-413.

Hill, T., Davis, A. and Roos, J., 2020. (PDF) Limitations of Fixed-Effects Models for Panel Data. [online] ResearchGate. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334000163_Limitations_of_FixedEffects_Model s_for_Panel_Data>.

Lindo, Jason M., Peter Siminski and Isaac D. Swensen (2018). College party culture and sexual assault. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10, pp. 236-265.

McCollister, K., French, M. and Fang, H., 2010. The cost of crime to society: New crimespecific estimates for policy and program evaluation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 108(1- 2), pp.98-109.

Moylan, C.A. and Javorka, M., 2020. Widening the lens: An ecological review of campus sexual assault. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(1), pp.179-192.

Miczek, K.A., Fish, E.W., De Almeida, R.M., Faccidomo, S. and Debold, J.F., 2004. Role of alcohol consumption in escalation to violence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036(1), pp.278-289.