Do Fair Trade Initiatives Help or Hinder Development

Do the systems and implementation of fair trade initiatives support or hinder development? How should we define development in this context? Is there a straightforward answer when considering economic, social, and institutional aspects of development?

By Julian Olsen-Pendergast

As the gap between developed and developing nations widens in the 21st century, we observe a shift in some consumer behaviour. While many consumers continue to prioritise consumption maximization, some consumers seek to ensure through their purchasing choices that producers are paid and treated fairly, and that production is socially and environmentally beneficial. Their aim is to contributes to efforts to combat poverty and global inequality. The increasing priority placed on social and environmental benefits of commodity production is reflected in the expansion of fair-trade initiatives which aim to promote development in developing countries (FAO, 2023).

Fair-trade initiatives try to address economic, social, and institutional underdevelopment by reshaping the terms of trade between consumers and producers (IEA, 2010). However, the impact of fair-trade initiatives is debated, with some arguing that rather than helping, they in fact hinder development (Collier, 2007).

This report examines evidence on the impact of fair-trade initiatives on development and assesses whether they help or hinder development. Fair-trade initiatives, often implemented through labelling and certification schemes, provide producers with ‘fair’ terms of trade and technical support. Fairer terms of trade include higher prices that cover production costs, a living wage for producers, and premiums for desirable environmental and social production characteristics, e.g. suitable working conditions, protection from exploitation and climate and/or nature positive commodity production (EFTA, 2013; Nunn, 2019).

To understand if these schemes help or hinder development, the term 'development' is defined. In this report, development is characterized by improvements in three broad areas: economic, social, and institutional. This report assesses whether empirical evidence supports the theory that fair-trade initiatives promote development in each of these areas.

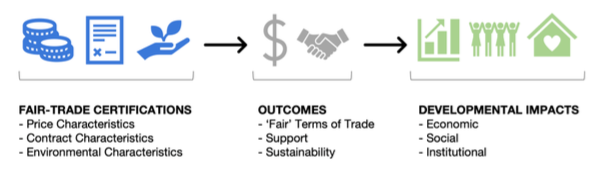

This section presents the theory underlying fair-trade initiatives and its impact on development. Fair trade initiative use various mechanisms, such as targeting price- setting, contract requirements and environmental standards, to influence exchange outcomes between producers and consumers, subsequently affecting development areas, as illustrated below:

Price Characteristics

1. Price Floor – A minimum price for a fair-trade good is set. This price is determined through the average costs of sustainable production and region-specific costs of living. In better cases, producers can also negotiate higher prices.

2. Premiums – Often called social premiums or community development premiums. These premiums represent a markup on the minimum commodity price. The amount of the premium may improve the livelihood of the producer, or it may be reinvested into community-level institutions or other socially desirable institutions.

Contract Characteristics

3. Credit Access - Provision for access to credit or advance crop financing is stipulated in contracts, allowing fair-trade producers to smooth consumption if their crop is seasonal.

4. Freedom to Associate and Working Conditions – Contracts may require that workers at fair-trade facilities work in safe and sanitary conditions and receive a wage that is equal to or higher than the legal, region-specific average or minimum wage.

5. Community Institutions – Contracts may support establishment of institutional structures where producers are encouraged to form independent associations or unions. Through joint decisions and cooperation, small producers can reduce transaction and processing costs.

6. Environmental Requirements – Contracts may require adherence to environmental standards, including, for example, the prohibition of environmentally harmful chemicals and use of genetically modified crops.

Some argue that, theoretically, these characteristics should contribute to promoting development in households and communities. This occurs through three broad mechanisms. Firstly, fair-trade initiatives boost economic development as revenue, access to credit, and income increase. Secondly, associated improvements in social development enhance gender equality and community trust, engagement, and empowerment. Lastly, initiatives contribute to institutional development by investing premiums in community infrastructure and resources (Dragusanu, 2014).

However, other academic literature argues that the theory on fair-trade initiatives promoting is flawed and that these initiatives are likely to hinder development. Firstly, the high costs of certification restrict smaller and poorer producers from participating. Acting as a barrier to entry, certification causes inefficiencies in the market by not being accessible for the most vulnerable producers in developing nations (Nunn, 2019). Further amplified by theoretically predicted negative selection biases, with factors such as experience, education, and lower-income influence access to certification (Zúñiga-Arias, 2009; Lumpach, 2016). Secondly, initiatives fail to address underlying systemic issues in developing nations' production economies. The promise of additional revenue from certification locks developing nations' producers into producing crops that will keep them in poverty due to their relatively low added value and productivity (Collier, 2007). Fairtrade initiatives fail to address the incentive changes that are needed to transform developing nations' economies.

The next section assesses whether the empirical evidence supports the theories that fair trade initiatives promotes or hinders economic, social, and institutional development.

It is argued that fair-trade schemes have a positive impact on economic development through higher and more consistent revenue and income, improved access to credit and payment in advance of sale. In theory, the higher prices, better contracts, and compensation for sustainable production practices benefit producers and economies more broadly. At the national level, there are positive impacts on economic development through three primary avenues: increased business profits, more accessible credit on better terms and increased wages and income levels.

Firstly, fair-trade initiatives in theory increase prices that producers sell their goods at through price floors and premiums. Higher price should increase revenue and long-run stability of production. Empirical evidence supports this. Dragusanu’s (2021) study on coffee production in Costa Rica found that coffee mills with fair- trade certification experienced positive economic effects. Under certification, mills sold more coffee and at higher prices, thereby increasing their revenue relative to coffee producers without certification. The benefits were further validated through macroeconomic effects analysis on exports, indicating that fair-trade initiatives directly stimulate economic growth in regions where they operate.

Secondly, fair-trade initiatives may increase producers’ ability to access credit and finance, and at lower cost due, to their higher income and to fairtrade contracts that provide for access to credit in advance of sale. Access to credit on reasonable terms is particularly important given the volatile and costly nature of borrowing in developing nations, where individuals often resort to informal lenders that charge ~40-200% interest on small and short-term loans (Aleem, 1993). Accessible credit at reasonable rates is vital for economic development. Empirical evidence suggests that fair-trade initiatives do indeed improve access to credit and at cheaper rates (Elder, 2012; Ruben, 2012).

Finally, fair-trade initiatives increase the incomes of employees of certified producers due to contract clauses that require producers to pay fair wages. However, empirical evidence indicates there is significant variability in income improvements. Research on black pepper farms in India and coffee farms in Nicaragua found that certification increased income and income per capita for production workers compared to non-certified farms (Parvathi, 2016; Pirotte, 2006). However, empirical analysis from Costa Rican coffee producers found no evidence that fair-trade certification increased the wages of unskilled coffee farmers, despite evidence of increased income for the owners of the coffee mills (Dragusanu, 2021).

However, what if the theory that initiatives act as barriers to entry and are only available to comparatively larger and more developed firms holds true? In that case, the economic development gains would potentially exacerbate the economic development divide in the local communities. Empirical evidence suggests that this is not the case, as findings indicate no statistically significant relationship between the accessibility of certification initiatives and pre-affiliation characteristics, such as income, size, or education (Becchetti, 2013; Dragusanu, 2021). Furthermore, Parvathi et al. (2006) found that, in the case of black pepper farmers in India, certification initiatives were more likely to be adopted by less educated farmers.

Moreover, do fair-trade initiatives address systemic challenges associated with developing country over-reliance on low-productivity and low-value-added agricultural outputs? While there is no empirical evidence to test this claim, assuming firms exit the agricultural sector if it remains low productivity and shift to more productive sectors, proxy empirical evidence indicates that fair-trade initiatives decrease the likelihood of industry exit (Dragusanu, 2021). This could potentially imply forgone opportunities for these firms to engage in more productive industries that could contribute to long-term economic development.

In summary, empirical evidence indicates that fair-trade initiatives play a positive role in fostering economic development. Despite concern that fair trade initiatives might perpetuate unproductive sectors through higher prices, fair trade producers are not receiving charity. Rather, they are obtaining a fair price for their goods without exploitation. Multiple studies on fair-trade certified producers provide evidence of improvements in access to credit at fair terms, revenue and income which contribute to economic development.

The second argument in favour of fair-trade initiatives is their positive impact on social development. The theory posits that initiatives contribute to improvements in communities’ social structures and wellbeing. In theory, initiatives should improve gender equality, community development, trust, and empowerment, providing marginalized groups with a platform to voice issues.

Firstly, fair-trade initiatives, in theory, should improve gender equality in the workforce through contract that require certified producers to uphold equal pay for all genders. Therefore, women in the communities of fair-trade producers should see improvements in their wages and, by extension, society should experience improvements in gender equality. In reality, evidence of progress in gender equality through fair trade initiatives (Elder, 2012; Taylor 2002; Utting-Chamorro 2005), indicates that improvements are relatively small compared to predicted values. Additionally, while studies find improvements in the wages of women working for certified producers, these improvements are based on increased working hours. There are also concerns related to equal access and opportunities for leadership roles for women within production organisations (Imhof 2007). However, studies have found evidence that initiatives promoting economic development reinforce developments to gender equality, thereby amplifying social development (Qian, 2008; Sharma, 2016).

Secondly, fair-trade initiatives theoretically promote social development through their impact on community trust and development. Under certification, producers are encouraged to form institutional structures to share administrative burdens and take advantage of economies of scale. These structures have been found to impact community trust and inclusion, as producers interact and build connections, boosting community bonding and spirit. This theoretical prediction is further substantiated by empirical findings showing that involvement in fair-trade initiatives develops local communities and networks through impacts on shared work and institutional meetings (Pirotte, 2006; Elder 2012).

Finally, fair-trade initiatives support the empowerment of marginalised groups and the conservation of cultural knowledge and history. When partnering with fair-trade organisations, indigenous producers, and local communities, are given a platform to voice issues, access to rights and inputs and help to ensure safe and sanitary working conditions, which help combat exploitation. Empirical evidence suggests that fair-trade initiatives can indeed provide indigenous and marginalized groups with a platform to voice issues surrounding social preservation and enable the preservation of historical and cultural methods (Pirotte, 2006; Overbeek, 2019). Additionally, studies have found that initiatives increase consumers' information on human rights violations and communities' ability to combat rights abuses (Le Mare, 2008).

Overall, there is significant empirical evidence to support arguments that fair-trade initiatives support social development, with positive findings regarding gender equality, community development, and improved representation and rights for marginalised groups. There is no empirical evidence that fair-trade initiatives hinder social development.

Finally fair-trade initiatives may support institutional development and stability within production areas. With certification, premiums potentially being reinvested in community institutions, boosting investment in local infrastructure, and education (FairTrade International, 2016).

Assuming that fair-trade premiums are reinvested in community infrastructure such as schools, health services, and storage facilities, the community should see improvements in this infrastructure and resulting improvements in standards of living and human development (Dragusanu, 2014). These investments should enhance a community’s ability to improve efficiency, productivity, and boost institutional development. In reality, studies indicate variable effects on development. Research in Rwanda, India, and Nicaragua finds statistically significant improvements to local community infrastructure in areas of certified production (Elder, 2012; Parvathi, 2016; Pirotte, 2006). However, other studies find effects on infrastructure are limited and below expected effects (Becchetti, 2013; Nunn 2019).

Additionally, if premiums are invested in schools, school supplies, or the provision of scholarships— theoretically this should result in a boost to educational variables such as school attendance and educational attainment. These improvements should support regional development as they improve human capital. However, this is not entirely supported by empirical findings. While for Chilean honey producers, the introduction of fair-trade initiatives improved community education systems (Becchetti 2013), for Costa Rican coffee producers, there was no evidence of improvements in enrolment. Moreover, evidence indicates some adverse effects for children of non-certified producers (Dragusanu, 2021).

However, schooling and learning should be differentiated. Schooling is not synonymous with learning, and enrolment is only one variable associated with education. Evidence suggests that investment in health services boost learning ability and indirectly supports education within communities (Lucas, 2010).

While fair-trade schemes do not appear to have as positive an impact as expected in theory, empirical evidence document positive development impacts to community institutions through improvements in community infrastructure and education.

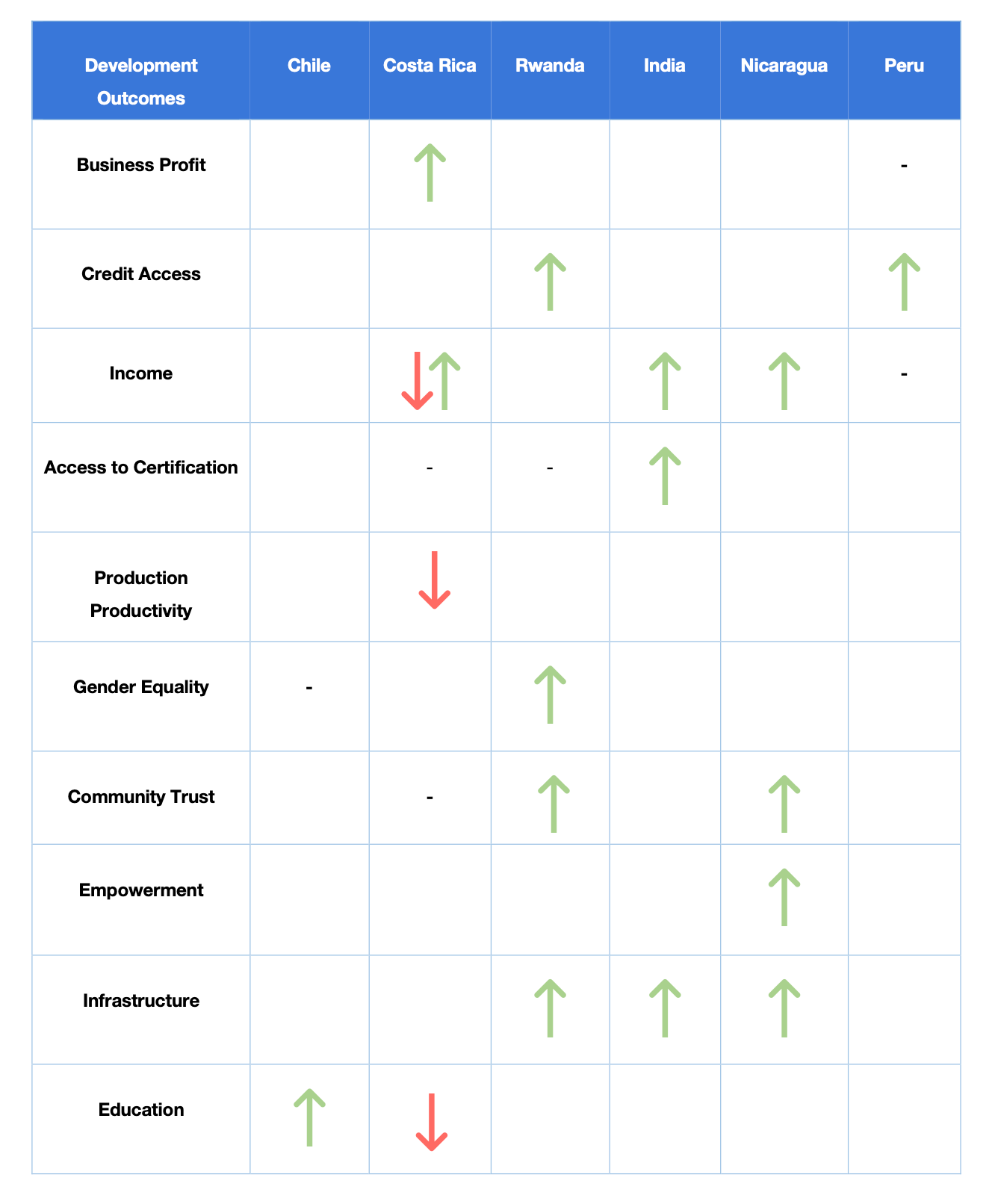

In conclusion, in theory fair-trade initiatives may promote positive gains in economic, social, and institutional development outcomes. Empirical research suggests that while the impact on development of fair-trade initiatives is less than predicted, there is evidence suggesting that fair-trade initiatives support development. The table below summarises whether empirical evidence finds a positive or negative impact of fair trade on development:

However, empirical papers predominantly focus on short-term development outcomes and to not consider long-term effects of fair trade initiatives on development. Additionally, the impact of fair trade on the environment and sustainability should be examined further (details provided in the appendix).

Evidence suggests that fair-trade initiatives as a whole support development and provide a valuable tool for ethical, mutually beneficial exchanges between producers and consumers.