Economics as Science of Exchange

What is the primary focus of economics? How have game theory and search/matching models advanced our understanding of exchange and partnership formation in economics? What are some of the main exchange mechanisms and institutions analysed in economic theory?

By: Dr Francis Kiraly

To paraphrase A. Marshall, economics is the study of human beings in the ordinary business of life. The day-to-day life of an individual mostly means having to interact with others in situations where there is scope for cooperation in the face of conflicting interests of various degrees.

Trade and partnerships (aimed at exchange) are the main forms of cooperation, and economics is the scientific study of these patterns. After all, "it is by treaty, by barter, and by purchase, that we obtain from one another the greater part of those mutual good offices which we stand in need of." (A. Smith: Wealth of Nations).

Economics investigates institutions of exchange: those alluded to by Smith (contracts, bargaining, and the price system), but also many other allocation mechanisms. The objective of economic theory is to provide explanations for and an understanding of the varied patterns in which cooperation through exchange partnerships occur in a free society—one where individuals have preferences, property rights are clear, and trade is voluntary.

At the most intuitive (deceptively trivial?) level, any exchange partnership requires the presence of the parties involved, as well as the prospect of a beneficial deal. In more technical terms, a match needs to form so that the parties can share the surplus. Viewed like this, it is quite obvious that the subject matter of economics has been with us since time immemorial.

But startlingly, it is only 80 years ago that we acquired appropriate methods for investigating all exchange patterns, and only 60 years since we started paying attention to search frictions that hamper partnership formation.

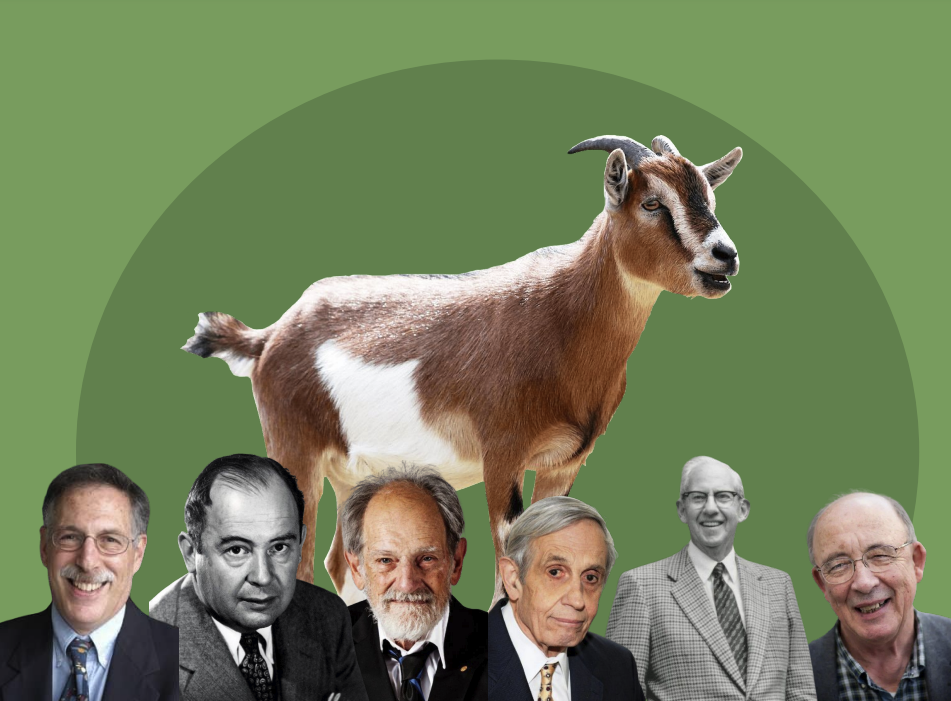

The first breakthrough came with the birth of game theory—the formal language of interactive decision-making. Its pioneers were the mathematical geniuses J. von Neumann, J. Nash, and L. Shapley. The second breakthrough originated in the development of search/matching models in the work of G. Stigler, P. Diamond, and D. Mortensen.

Consider the quintessential example of exchange between an owner of a goat and a prospective buyer. A sale can only occur if the two parties find each other, but this very often takes time, effort, and luck. How they look for each other, and how their coming together depends on the number of other traders on both sides of the market, can only be analyzed using search/matching models.

In turn, once the "partnership" is formed, how do they share the surplus? What will be the terms of trade? One is tempted to answer that they will negotiate a selling price, or that the seller, possibly not knowing the valuation of the buyer, may decide to post a take-it-or-leave-it asking price. Alternatively, the seller may set up an auction if contacted by several buyers. While we always had anecdotal knowledge about haggling, pricing with incomplete information, and auctions, game theory meant we could now undertake a rigorous examination of these forms of exchange.

Before game theory and search/matching models, economists inhabited the Walrasian planet that had no search frictions and a price system as the only trade-coordinating mechanism. We truly resembled those who keep looking for their lost keys only under the street lamp.

These days, it is much more fun: we walk around with a pair of powerful torches! Even if one ignores the allocation of free goods and "delegated" allocation through voting or dictatorship, we are able to say a lot about all other exchange mechanisms: explicit contracts, social norms (implicit contracts), auctions, pricing, bargaining and arbitration, crime and fraud, matching and assignment, renting, queuing, bequest, bribery, tipping, even allocation by chance.