Some Serious Satire - The Onion's Supreme Court Brief

What is The Onion, and what does it have to do with the U.S. Supreme Court? How has the case of Novak v. City of Parma changed parody and satire publications? How does an amicus brief attempt to protect humorists from felony charges?

By: Julian Olsen-Pendergast

For those readers who are unfamiliar with the hilarious parody news publication, The Onion, let me provide some quick background. The self-proclaimed "America's Finest News Source" is a newspaper organization that publishes some of the funniest and wittiest satirical articles on supposed breaking news. Aside from comedic parody of news and media conglomerates, their head writer, Mike Gillis, and a team of lawyers recently filed their first amicus brief to none other than the U.S. Supreme Court.

An amicus brief is a legal document filed by a non-party, providing information and arguments in support of the defendant or the plaintiff in a court case to assist the court in its decision-making process. In this case, the non-party, The Onion, is providing information and arguments in support of Anthony Novak in the case Novak v. City of Parma.

In March of 2016, Anthony Novak created a Facebook page with the same name, profile, and cover picture as his local police department, the Parma Police Department. Of course, the page was not certified as the official page, nor was it claiming to be, as it was clearly a "community" page, with the about section of the page reading "We no crime." For context, Parma, the biggest suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, has grown the reputation of being a little extra. And by extra, I mean to say it has a well-documented problem with racism, with the Department of Justice concluding that "the City of Parma has engaged in a pattern and practice of racial discrimination." In addition, the Parma Police department has been cited for refusing to hire minority police officers. Those familiar with the department will know they are notorious for prosecuting black drivers for driving while being black.

Bringing us back to Novak's Facebook page, where over a period of 6 hours he posted 6 satirical posts. The first was an apology on behalf of the Police Department for:

"neglecting to inform the public about an armed white male who robbed a Subway sandwich shop" while promising to bring to justice an "African American woman" who was loitering outside the Subway during the robbery.

Or an announcement informing citizens about the new Department hiring process where:

"The test will consist of a 15-question multiple-choice definition test followed by a hearing test" and "strongly encouraging minorities to NOT apply."

Or with an announcement about an upcoming pedophile reform event in which the department would:

"Anyone who passes all of the stations will be removed from the sex offenders registry and accepted as an honorary police officer of the Parma Police Department."

In response, the Police Department issued a statement warning citizens of the parody account and subpoenaed Facebook to get the account holder's information. After searching for a crime to fit the situation, the Parma Police Department landed on claiming that Novak disrupted public services by "knowingly using any computer systems to disrupt, interrupt, or impair the functions of police governmental operations." Claiming that the 11 phone calls they received concerning the fake account disrupted public services, a 4th degree felony (maximum penalty of 18 months in prison).

However, Novak stood trial and fortunately, the jury acquitted him of the felony. Subsequently, suing the City of Parma, Police Department, and police officers for violating his civil rights (which they did). However, the police officers raised 'Qualified Immunity," bringing us to where The Onion's brief comes into play.

Qualified Immunity protects state officials from being held accountable for violating a person's constitutional right if a court has not previously stated that the officer's act was unconstitutional. It is only circumvented if the violation is "clearly established." In non-lawyer speak, it means if an average officer would probably know that they were violating constitutional rights while doing it.

So they claimed that some of the aforementioned Facebook posts could be reasonably understood as not parody, not protected, and fair grounds for probable cause. And this is what The Onion took issue with.

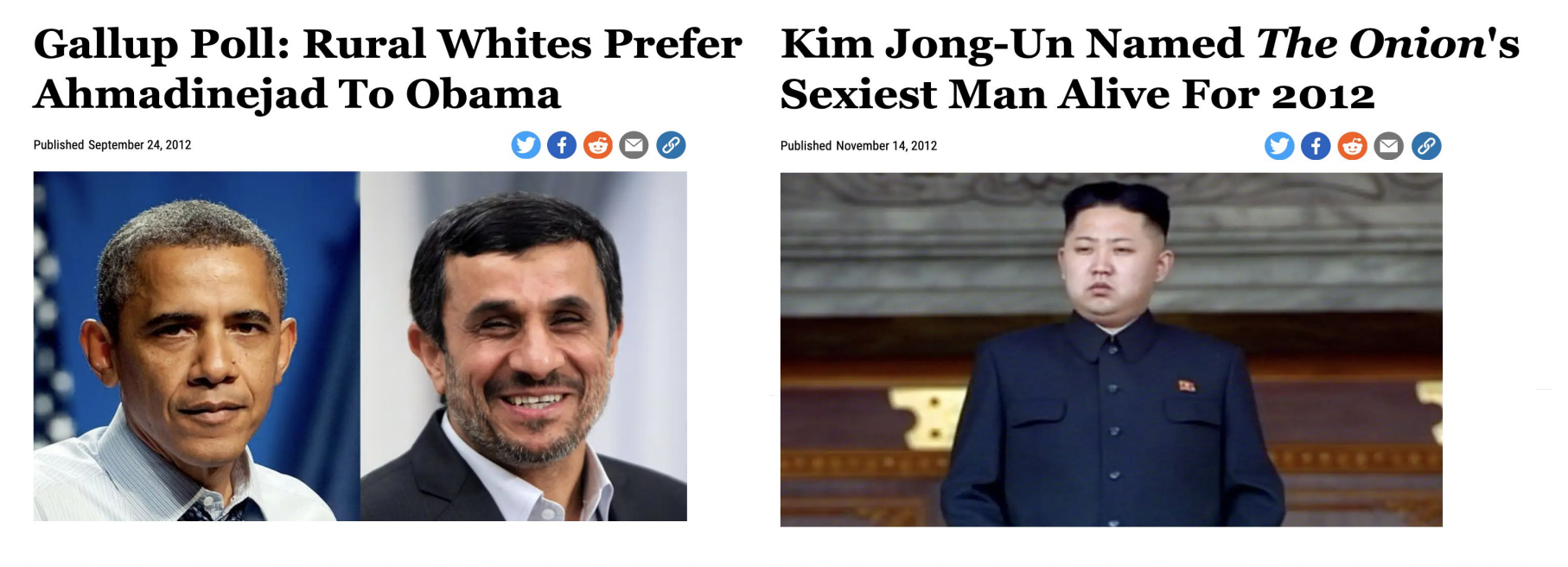

The brief starts out by discussing the interests of The Onion in this case, where The Onion gives background on their "highly acclaimed" and "universally revered" publications, even stating that their "fact-driven" reportage has been favorably cited by Iran and Chinese state-run media. In which the two news headlines below were mistaken by Iran and Chinese state-run media respectively as true stories and republished.

In subsequent sections, The Onion laid out the reason they filed the amicus brief, stating that:

The Onion files this brief to protect its continued ability to create fiction that may ultimately merge into reality. As the globe’s premier parodists, The Onion’s writers also have a self-serving interest in preventing political authorities from imprisoning humorists. This brief is submitted in the interest of at least mitigating their future punishment.

Additionally, zeroing in on the police department's claim stating that without a disclaimer the police officers can be protected against violating civil rights of free speech as defeating the essence of parody. As some forms of comedy don’t work unless the comedian is able to tell the joke with a straight face. Parodists intentionally inhabit the rhetorical form of their target to exaggerate or implode it—and by doing so demonstrate the target’s illogic or absurdity. Put simply, for parody to work, it has to plausibly mimic the original.

Therefore, making Qualified Immunity null and void in the case for parodists, as the average officer does not need to be told explicitly what they have no serious trouble figuring out for themselves. And the lack of an explicit disclaimer makes no difference to whether a reasonable reader would discern that this speech was parody.

To reinforce this point, the brief includes a section of "gripping legal analysis" to ensure that every jurist who reads this brief is appropriately impressed:

Bona vacantia. De bonis asportatis. Writ of certiorari. De minimis. Jus accrescendi. Forum non conveniens. Corpus juris. Ad hominem tu quoque. Post hoc ergo propter hoc. Quod est demonstrandum. Actus reus. Scandalum magnatum. Pactum reservati dominii.

A clear joke making fun of the convoluted nature of lawyers and the way they speak. It would not have worked quite as well if they outright said at the start of the joke:

Hello there, reader, we are about to write an amicus brief about the value of parody. Buckle up because we’re going to be doing some fairly outré things, including commenting on this text’s form itself!